5 other psychology undergraduates and I studied the effects of advertisements on participants ability to retain information, in a non-IRB approved "practice" experimental setting.

Introduction

The internet has changed the way we do everything, including the way we advertise. Advertisements were initially used to make potential customers aware of the available goods and services that a company had to offer. In today’s market advertising has evolved into a multi-billion dollar industry that goes beyond informing, persuading and influencing the consumers. Reading the news, doing research for school, or browsing the web has become an arduous task of navigating around advertisements to find the desired content. According to Foroughi, et al.’s (2015) research, the various disruptive effects of online advertisements were shown to negatively affect the necessary basic processing required to successfully connect and synthesize subsequent information required for text comprehension. Rawson’s & Touron’s (2009) work goes into further detail about how people absorb and comprehend information. The information gained from Rawson’s & Touron’s work aided our study in understanding the context of reading comprehension as a whole and in developing context-aware applications for our study. Our aim is to evaluate the effects of the levels of distractions (i.e. advertisements) on reading comprehension measured through time and score on a given comprehension test. Researchers Robison, & Unsworth (2015) found in their study that reading comprehension rates improved when participants’ focus was greater. Smith’s (2011) discovery that narrative distractions sped up grammatical judgement showed that auditory distractions were helpful in comprehension, but these distractions were in the form of music. We believe that visual distractions, and especially advertisements, will prove to actually be detrimental to comprehension, rather than enhance it in the way that music does.

We want to see whether two levels of distraction (advertisements) would affect a person’s ability to absorb information from an online source as quickly and efficiently as if there were no advertisements distracting them. Ecker’s, et al., (2014) study showed that readers are generally affected by the external information surrounding the article they are reading. We hypothesize that students who read information with high distractions in the form of advertisements would have lower reading comprehension (take more time and answer fewer questions correctly) than the students who read information with fewer or no distracting advertisements present. Thus, we believe that more distractions would result in less comprehension of material.

Methods

Participants:

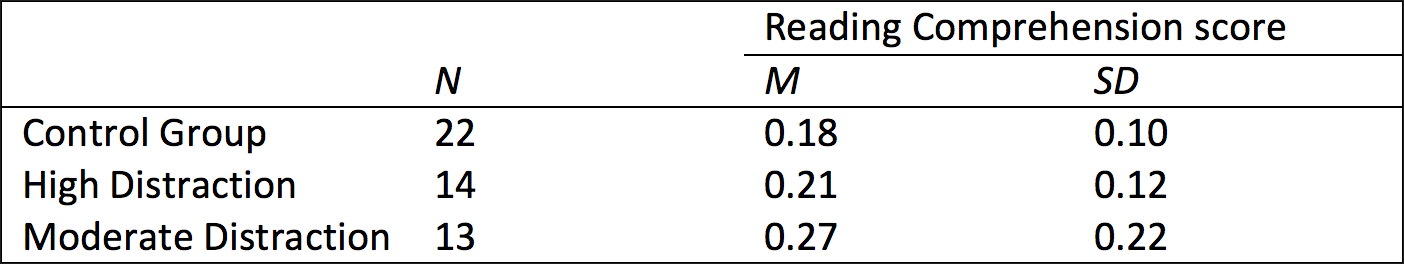

Our participants were 49 undergraduate students selected from three experimental methods lab classes at the University of North Texas. Our groups were composed of 22 students in the control group, 13 in the “moderate distraction” group, and 14 in the “high distraction” group. The groups were based on class attendance of three different lab sections. We divided our participants into three groups; Group 1 consists of 20 females and 2 males as our control group, Group 2 consists of 11 females and 3 males as our “high distraction” group, and Group 3 consists of 8 females and 5 males as our “moderate distraction” group.

Measures

We measured participants’ reading comprehension with the reading comprehension practice test (see Appendix A), in which participants read a short story and answered 7 multiple-choice questions designed to test their retention of the material (Reading Comprehension Test; Morrison, 2015). Comprehension was measured on two levels: time elapsed and accuracy scores (by percent). We used these scores to create our reading comprehension score by dividing the percentage score by the time elapsed (Accuracy/Time). Higher scores and lower time elapsed represent greater comprehension.

Procedure

IRB approval was obtained prior to the experiment. Informed consent forms were signed and collected, and then participants were directed to an online survey which contained a link to a separate website, as well as 7 multiple-choice questions. The website presented participants with a short story and varying degrees of distractions. The story and multiple-choice questions were taken from the reading comprehension practice test (see Appendix A). The control group, composed of 22 students, was given a site with only the story presented, and no distractions (Appendix A, Figure 2). The moderate distraction group, with 13 students, was linked to a site with a large banner advertisement across the top, and minimal advertisements toward the bottom of the page (Appendix A, Figure 3). The high distraction group, with 14 students, was given a site with several advertisements distributed throughout the page (Appendix A, Figure 1). Participants were allowed to take as much time as needed, and were given no restrictions as to whether they could refer back to the story while taking the test. Scores (percent correct) and amount of time each participant used to complete the test were recorded via a third party online test creation site. After all participants had completed the test, as indicated when they exited the site and returned to the computer desktop, they were handed a debriefing form, which was reviewed aloud. No deception was used.

Results

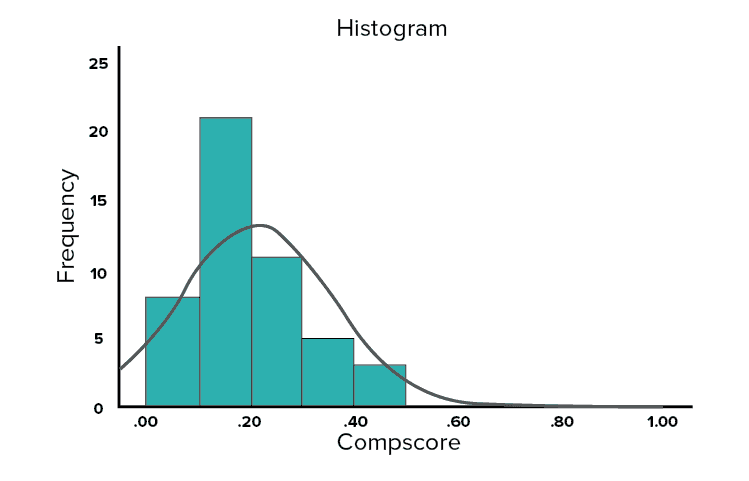

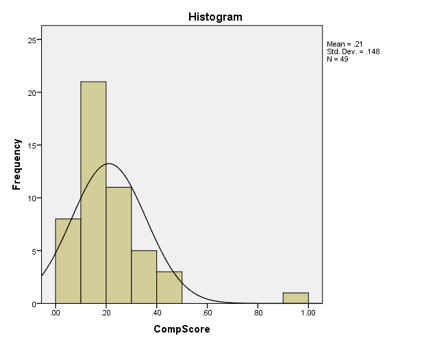

We conducted a one way ANOVA test to compare our control group and our two experimental groups, whom we exposed to different levels of distractions and subsequently given a test to measure their comprehension level. We found that our Levene’s test was not significant and equal variances are assumed, therefore F (2, 46) = 1.45, p = .245. Thus, we did not find homogeneity of variances.

Our test did not yield significant results to support our hypothesis and we cannot discard the null hypothesis. Our first group was our control group, which consisted of 22 participants (M = .18, SD = 0.10) who did not receive any sort of distraction in order to compare the outcomes to our experimental groups. In comparison, our control group got the lowest test scores and highest times. Group 2 was our experimental group with 14 participants (M = .021, SD = 0.12), whom we exposed to high levels of distractions with the second best scores out of the three groups. Group 3 had 13 participants who we exposed to a medium amount of distraction levels (M = 0.27, SD = 0.22) and had the best scores out of all the groups. However, there were no significant results found among the groups f(2, 46) = 1.67, p = .200. We used Least Squares Difference (LSD) as our post hoc test and our results were η2 = .07.

Note. * indicates statistically significant difference in mean scores as calculated by LSD test, p < .05.

Discussion

We hypothesized that students who read information with high distractions in the form of advertisements would have lower reading comprehension (take more time and answer fewer questions correctly) than the students who read information with fewer or no distracting advertisements present. According to our data, the level of distraction did not significantly lower the reading comprehension scores of our participants. The amount of distractions did not have a significant impact on the time and scores. Therefore, our hypothesis was not supported.

We utilized the research of Foroughi’s, Werner’s, Barragán’s, & Boehm-Davis’s 2015 study, Interruptions Disrupt Reading Comprehension, choosing animated graphics and pop-up ads which were similar to the distraction used in this study. According to our data, the distraction did not significantly lower the reading comprehension scores. We incorporated a validation check question into our quiz to identify a possible underlying hidden component that could threaten the validity of our quiz; we instructed our participants to choose one specific answer option regardless of their own preference / opinion. Our results indicated a large majority of inattentive respondents, which could perhaps explain the dissimilarity in our results. However, unlike Foroughi et. al’s 2015 study, we did account for timing. We incorporated a hidden timer on the online quiz which measured the overall time participants spent answering the questions on our quiz. Some of the distractions, i.e. advertisements, were vastly different from the content of our quiz. This may have had an influence similar to the effect of Ecker, Lewandowsky, Chang & Pillai’s 2014 study, The Effects of Subtle Misinformation in News Headlines. Unlike Ecker et. al’s 2014 study, we decided to develop our quiz online to control for the possible bias that some people might have for newspaper being a credible source.

It is also important to note our use of previous published research studies of Rawson’s & Touron’s 2009 study, Age Differences and Similarities in the Shift from Computation to Retrieval during Reading Comprehension, and Smith’s 2011 Study, Attention, Working Memory, and Grammaticality Judgment in Typical Young Adults. These previous theoretical frameworks taught us that experience with advertisements was in fact the best filter for advertisements. This coincided with our data, as the distraction did not significantly lower the mean reading comprehension scores. However, unlike Smith’s 2011 study we did not account for or control for people listening to music while taking our quiz. According to this study, it might actually have had an impact on response times and reading comprehensions.

limitations

The present study did not examine the restriction of demographics, the nonequivalent group sizes of our participants, the difficultly level of our quiz, and the possible inaccuracy of time recorded due to the mechanics of our quiz. We believe that the difficultly of the quiz and the possibility of inaccurate time recorded during the course of the quiz contributed to the negative skew of our results. With the lack of demographics of our participants, our quiz may not be an appropriate measure for the local population. Furthermore, in a one-way ANOVA unequal sample sizes can affect the homogeneity of variance assumption.

Areas for future research

Future researchers might consider whether animated and interactive advertisements vs. stagnant advertisements over repeated exposures may in fact lower the rates of the reading comprehension scores. Web designers and companies looking to utilize ad revenues online may want to consider whether or not it is more efficient to have a single advertisement on a website page by itself over having an advertisement on a web page that already has multiple advertisements present.

References

Ecker, U. H., Lewandowsky, S., Chang, E. P., & Pillai, R. (2014). The effects of subtle misinformation in news headlines. Journal Of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20(4), 323-335. doi:10.1037/xap0000028

Foroughi, C. K., Werner, N. E., Barragán, D., & Boehm-Davis, D. A. (2015). Interruptions disrupt reading comprehension. Journal Of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(3), 704-709. doi:10.1037/xge0000074

Morrison, Enoch. "Reading Comprehension Practice Test." Reading Comprehension Practice Test. Test Prep Review, n.d. Web. 24 Oct. 2015.

Rawson, K. A., & Touron, D. R. (2009). Age differences and similarities in the shift from computation to retrieval during reading comprehension. Psychology And Aging, 24(2), 423-437. doi:10.1037/a0016044

Robison, M. K., & Unsworth, N. (2015). Working memory capacity offers resistance to mind wandering and external distraction in a context specific manner. Applied Cognitive Psychology, doi:10.1002/acp.3150

Smith, P. A. (2011). Attention, working memory, and grammaticality judgment in typical young adults. Journal Of Speech, Language, And Hearing Research, 54(3), 918-931. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0009)